module ControlFlowDemo where

import LazyPPL

import LazyPPL.SingleSite

import LazyPPL.Distributions

import Control.Monad

import Graphics.Matplotlibprior1 :: Prob (Bool,Bool)

prior1 =

do x <- bernoulli 0.5

y <- if x then bernoulli 0.4 else bernoulli 0.7

return (x,y)x changes, y has to change too, and vice

versa.

model :: Prob (Bool,Bool) -> Meas Bool

model prior =

do (x,y) <- sample prior

score (if x==y then 1 else 0)

return xThe posterior probability of (model prior1) returning

true is 4/7.

Since x and y are correlated, it is not a

good idea to use a naive Metropolis Hastings simulation. But this is an

extreme example, and less extreme examples might appear in more complex

probabilistic programs that do benefit from Metropolis Hastings

simulation, where the correlations are not known in advance.

prior2 :: Prob (Bool,Bool)

prior2 =

do x <- bernoulli 0.5

ytrue <- bernoulli 0.4

yfalse <- bernoulli 0.7

return (if x then (x,ytrue) else (x,yfalse)) Of course, we could solve this particular program analytically. The point is rather that we have a universal program transformation manipulation that could be applied automatically.

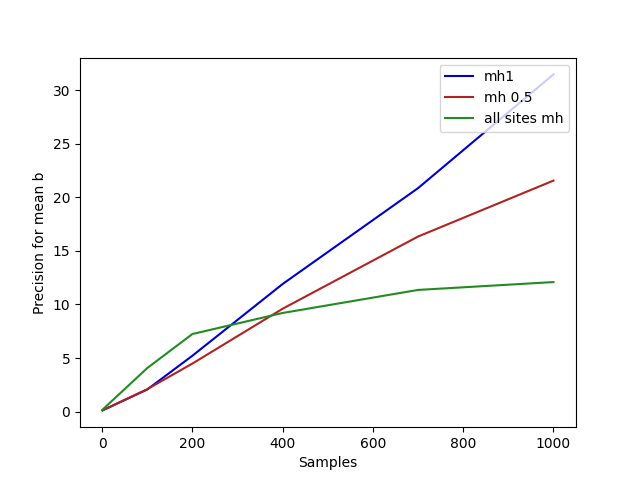

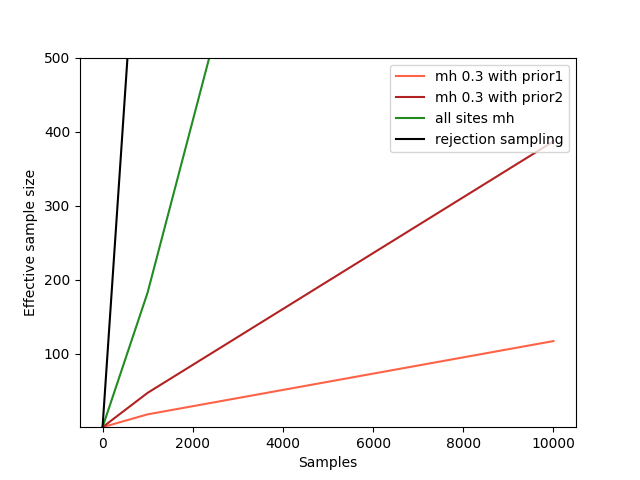

The following chart shows that the effective sample size (the ratio between the variance of a single true sample and the variance among the generated samples) is much better with this second implementation of the prior, although Metropolis Hastings is still far from optimal for this contrived problem.

-- Take a sampler (m) returning reals, regarded as an estimator,

-- and calculate the mean and precision for the estimator.

-- k is the number of samples to use in the estimator.

-- n is the number of runs to average over to approximate the mean, variance and ess.

meanPrec :: IO [(Double,a)] -> Int -> Int -> IO (Double,Double)

meanPrec m n k =

do xwss <- replicateM n m

let as = map ((\x -> x / (fromIntegral k)). sum . map fst . take k) xwss

let mean = (sum as) / (fromIntegral n) -- sample mean

let var = (sum (map (\x -> (x - mean)^2) as)) / (fromIntegral n) -- sample variance

return (mean,1/var)plotESSA =

do putStrLn "Plotting images/controlflow-essA.png..."

let xs = [1,1000,10000]

-- A rejection sampler where the scores are known to be 0 or 1.

let rejectionsampler m = fmap (filter (\(_,w) -> w>0.00001)) $ weightedsamples $ m

let truevar = (4.0/7.0) - (4.0/7.0)^2 -- variance for one true sample

-- Tests to plot

as <- forM xs $ fmap (\(_,prec)->truevar*prec) . meanPrec (mh 0.3 $ fmap fromBool $ model prior1) 100

cs <- forM xs $ fmap (\(_,prec)->truevar*prec) . meanPrec (mh 0.33 $ fmap fromBool $ model prior2) 100

es <- forM xs $ fmap (\(_,prec)->truevar*prec) . meanPrec (mh 1 $ fmap fromBool $ model prior1) 100

fs <- forM xs $ fmap (\(_,prec)->truevar*prec) . meanPrec (rejectionsampler $ fmap fromBool $ model prior1) 100

file "images/controlflow-essA.png" $

plot xs as @@ [o2 "label" "mh 0.3 with prior1", o2 "color" "tomato"] %

plot xs cs @@ [o2 "label" "mh 0.3 with prior2", o2 "color" "firebrick"] %

plot xs es @@ [o2 "label" "all sites mh", o2 "color" "forestgreen"] %

plot xs fs @@ [o2 "label" "rejection sampling", o2 "color" "black"] %

ylim (1::Double) (500::Double) %

xlabel "Samples" % ylabel "Effective sample size" % legend @@ [o2 "loc" "upper right"]

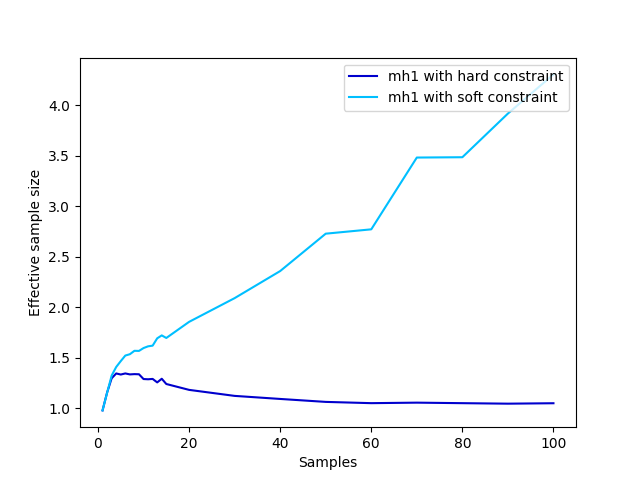

putStrLn "done."mh1): the first

implementation of the prior is especially bad, because all

proposals will be rejected except perhaps one. This irreducibility

arises from the hard constraints (scores of 0) and is

avoided to some extent with a softer constraint:

softModel :: Prob (Bool,Bool) -> Meas Bool

softModel prior =

do (x,y) <- sample prior

score (if x==y then 0.9 else 0.1)

return x

fromBool b = if b then 1.0 else 0.0

plotESSB =

do putStrLn "Plotting images/controlflow-essB.png..."

let xs = [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,20,30,40,50,60,70,80,90,100]

let truevar = (4.0/7.0) - (4.0/7.0)^2 -- variance for one true sample

-- Tests to plot

as <- forM xs $ fmap (\(_,prec)->truevar*prec) . meanPrec (mh1 $ fmap fromBool $ model prior1) 1000

bs <- forM xs $ fmap (\(_,prec)->truevar*prec) . meanPrec (mh1 $ fmap fromBool $ softModel prior1) 1000

file "images/controlflow-essB.png" $

plot xs as @@ [o2 "label" "mh1 with hard constraint", o2 "color" "mediumblue"] %

plot xs bs @@ [o2 "label" "mh1 with soft constraint", o2 "color" "deepskyblue"] %

xlabel "Samples" % ylabel "Effective sample size" % legend @@ [o2 "loc" "upper right"]

putStrLn "done."linreg :: Meas (Double,Double)

linreg =

do

a <- sample $ normal 0 3

b <- sample $ normal 0 3

let dataset = [(0,5), (0.1,10), (0.2,0)]

mapM (\(x, y) -> score $ normalPdf (a*x + b) 0.5 y) dataset

return (a,b)

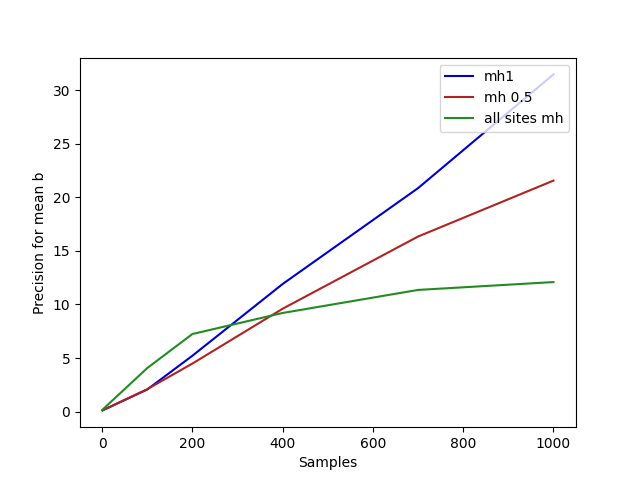

(Here we plot precision, which is proportional to effective sample

size, because a general effective sample size analysis isn’t written

yet.)

plotPrec =

do putStrLn "Plotting images/controlflow-prec.png..."

let xs = [1,100,200,400,700,1000]

-- Tests to plot

as <- forM xs $ fmap snd . meanPrec (mh 0.5 $ fmap snd $ linreg) 1000

bs <- forM xs $ fmap snd . meanPrec (mh1 $ fmap snd $ linreg) 1000

es <- forM xs $ fmap snd . meanPrec (mh 1 $ fmap snd $ linreg) 1000

file "images/controlflow-prec.png" $

plot xs bs @@ [o2 "label" "mh1", o2 "color" "mediumblue"] %

plot xs as @@ [o2 "label" "mh 0.5", o2 "color" "firebrick"] %

plot xs es @@ [o2 "label" "all sites mh", o2 "color" "forestgreen"] %

xlabel "Samples" % ylabel "Precision for mean b" % legend @@ [o2 "loc" "upper right"]

putStrLn "done."main = do

plotESSA

plotESSB

plotPrec